Atlas Antiques |

Email: joshatlasantiques@gmail.com Web site: https://www.atlasantiques.co.uk/ |

|

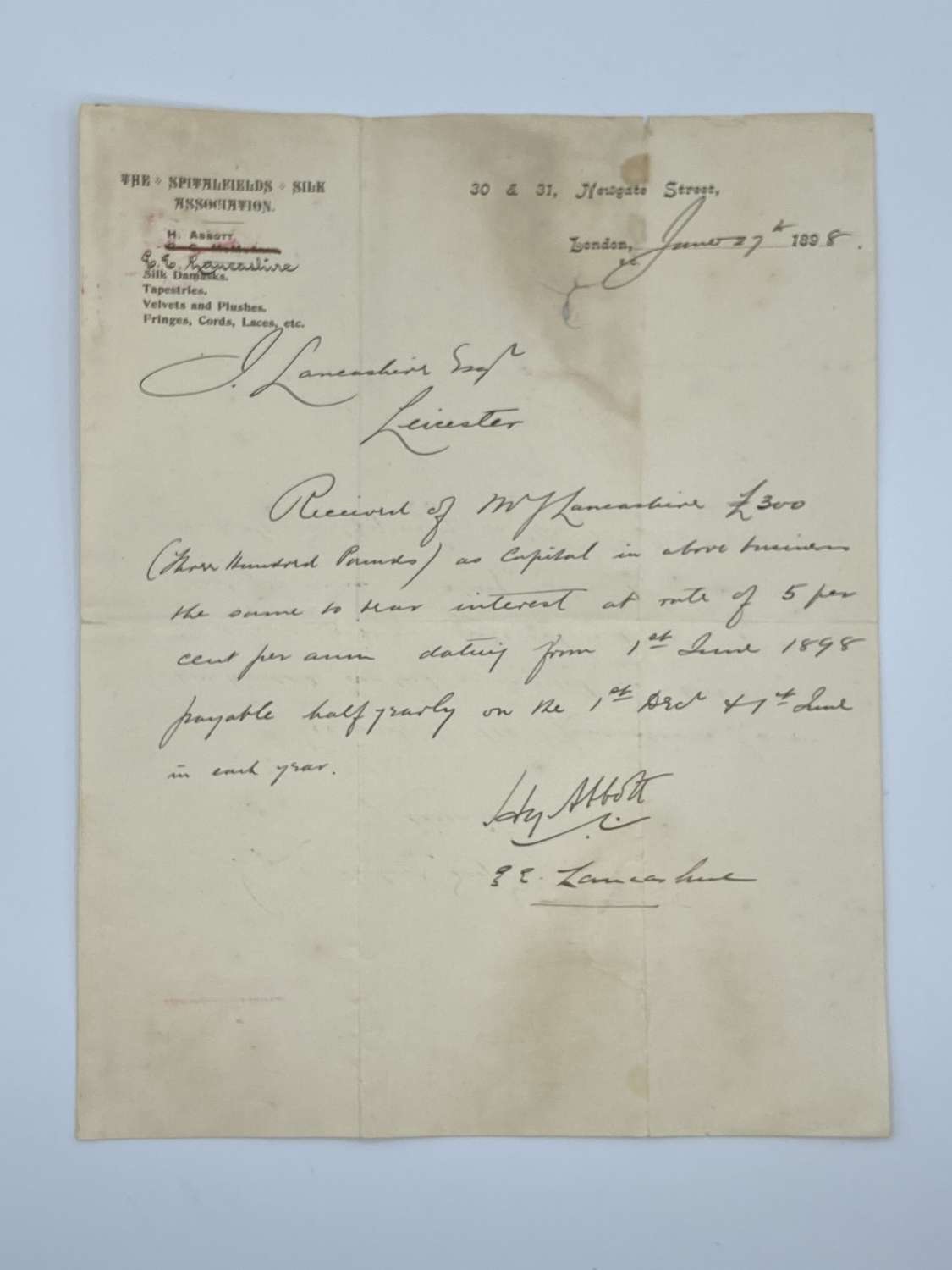

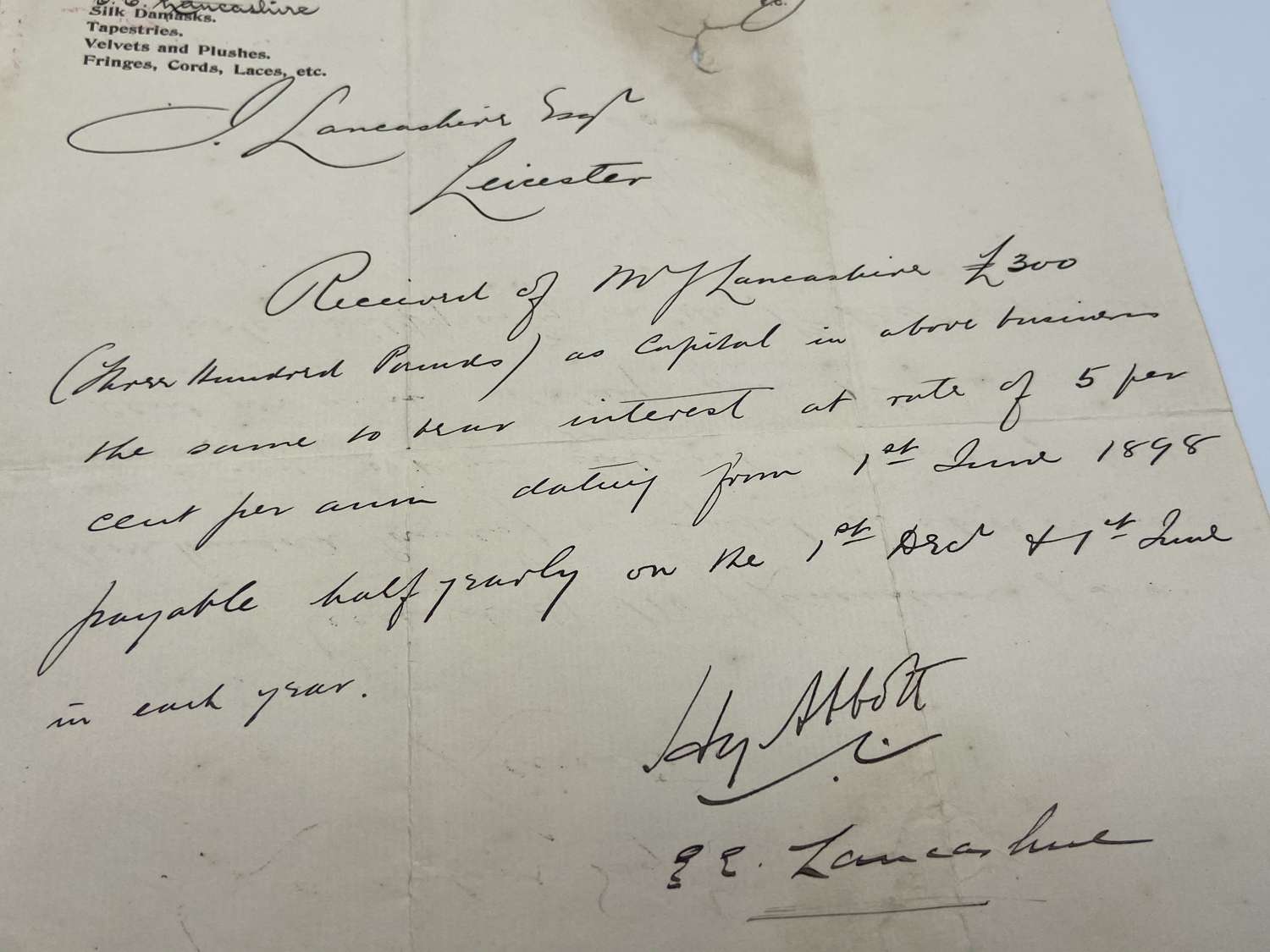

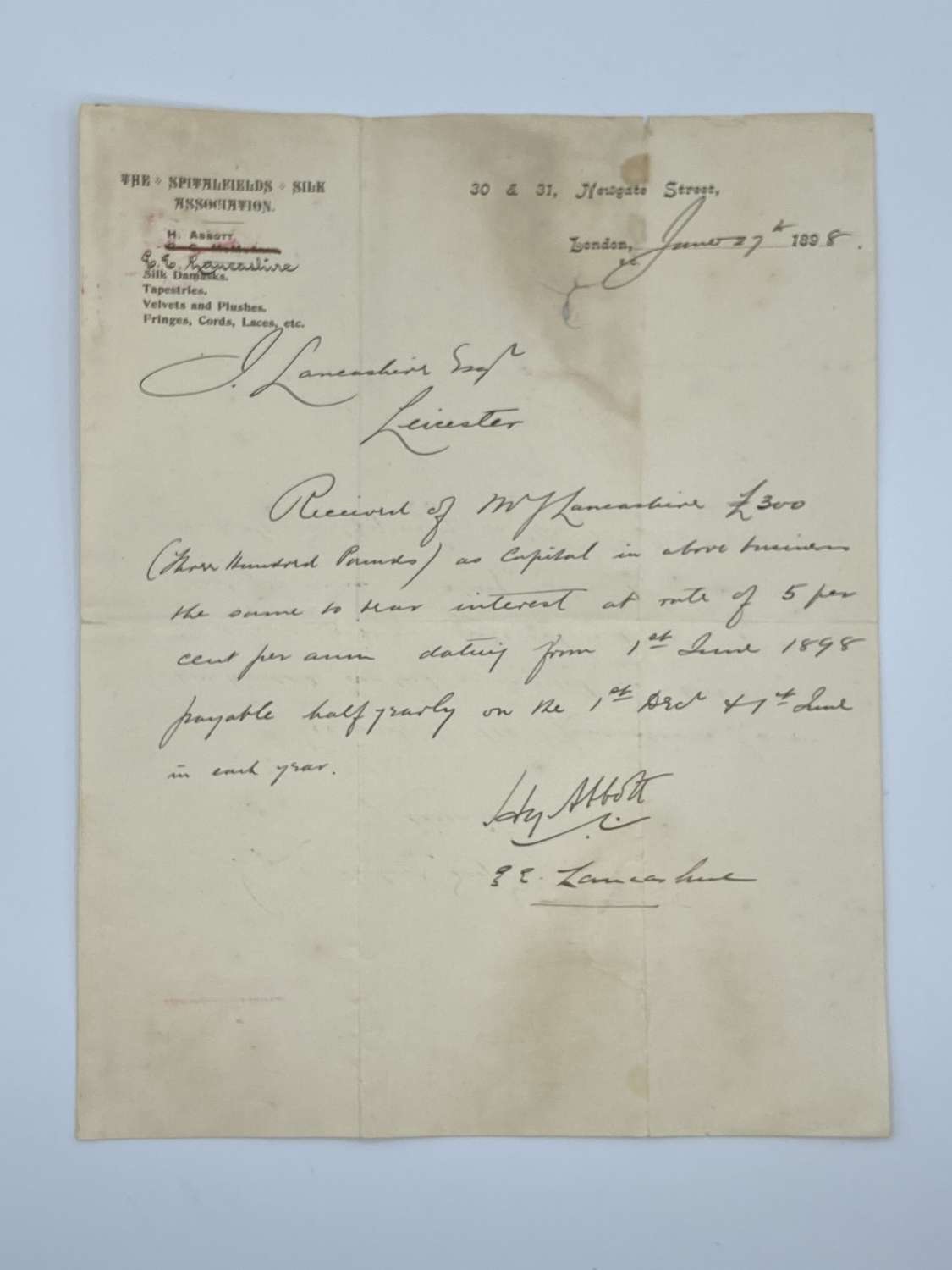

Code: 11164

For sale is an incredibly Rare Victorian Letter DatedJanuary 29th 1898 of a business agreement sent by the The Spitalfields Silk Association, through H Abbot, 30 & 31 Newgate street London, to a J Lancashire. Which is hugely important to London’s social history. Where there talking of a business agreement of £300 as capital in an above agreement (which isn’t present) and a deal on on a 5% commission on each deal, which would be made annually on the 1st of December and the 1st of June every year, in which underneath this agreement is signed is both of there names/ signatures. Below the letter is some context for this letter, the only documents like this are currently kept protected in the British museum collection. Weaver and Warehouse-man’ Joshua Warne was the master responsible for 30 & 31 Newgate street London.

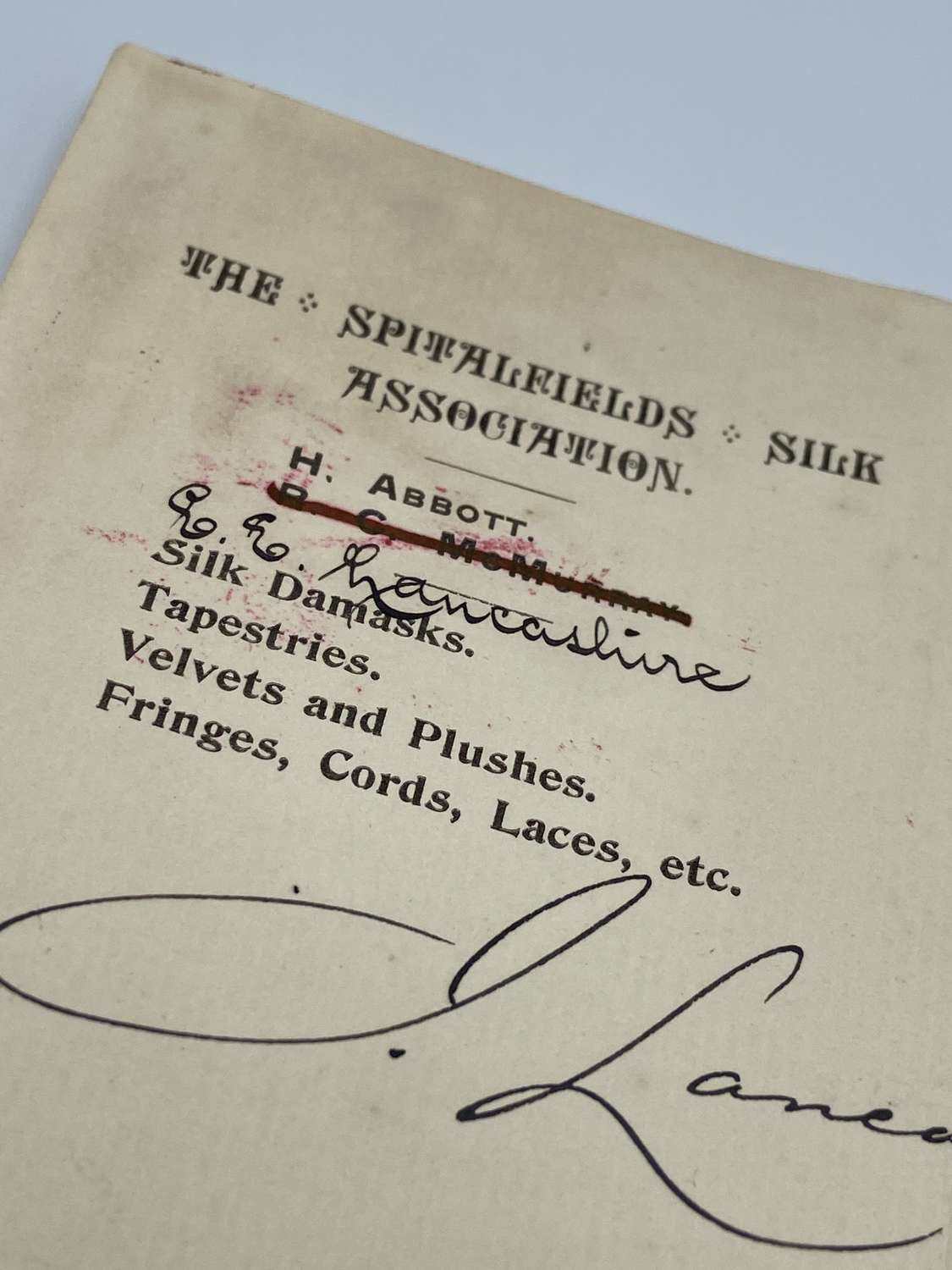

Top left is typed and states:

THE SPITALFIELDS SILK

ASSOCIATION,

H Abbott,

E E Lancashire.

Silk masks,

tapestries

Velvets and plushies. Fringes, cords, laces etc.

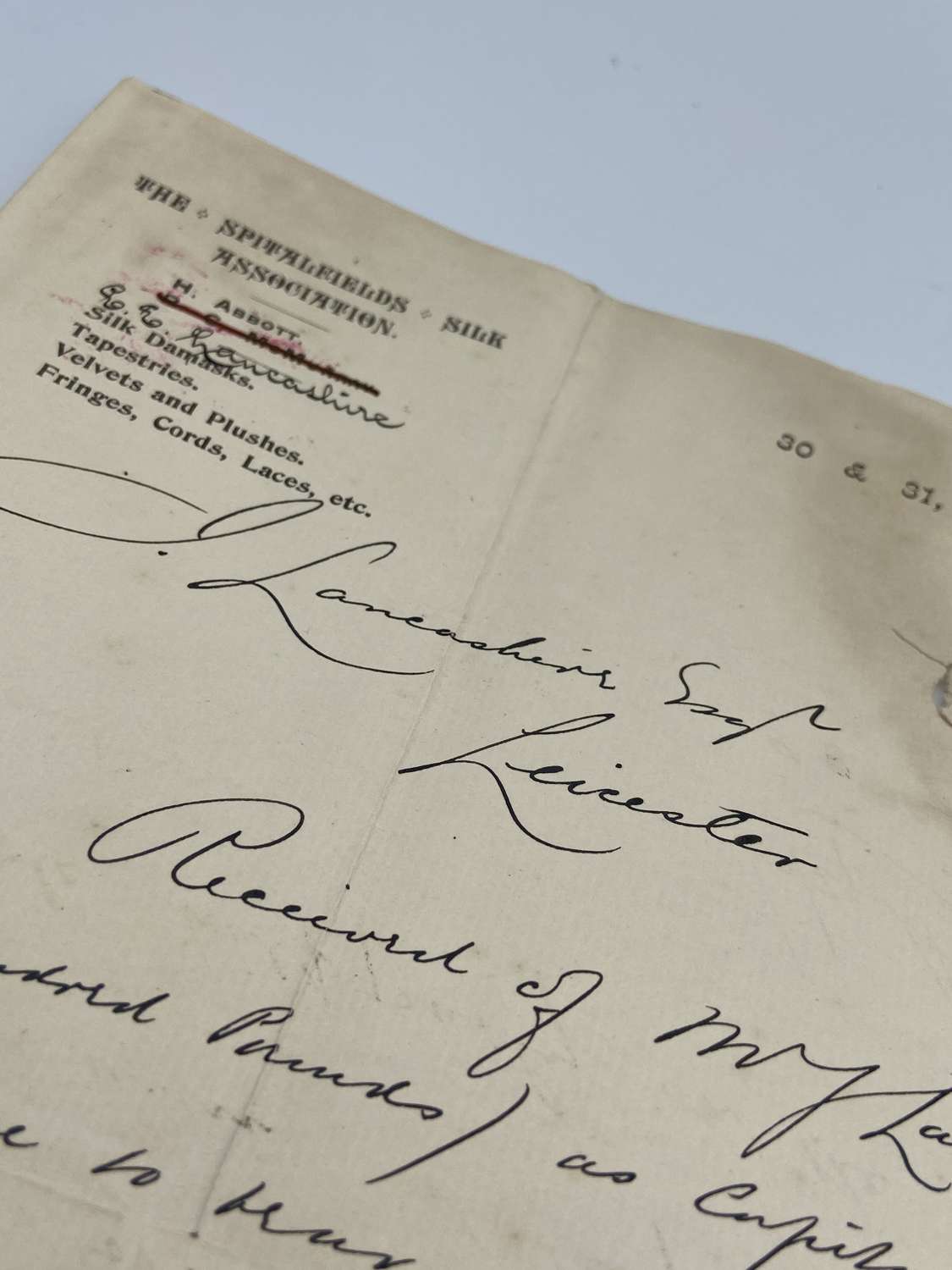

The top right states:

30 & 31 Newgate Street. ,

London June 27th 1898

The rest of the letter is then done by hand and states the following:

J. Lancashire’s of Leicester

Received of my Lancashire £300 (three hundred pounds) as capital in above businesses. The same to hear intrest at rate of 5% per annum daily from 1st June 1898 payable half as early on the 1st and the 2nd in each year,

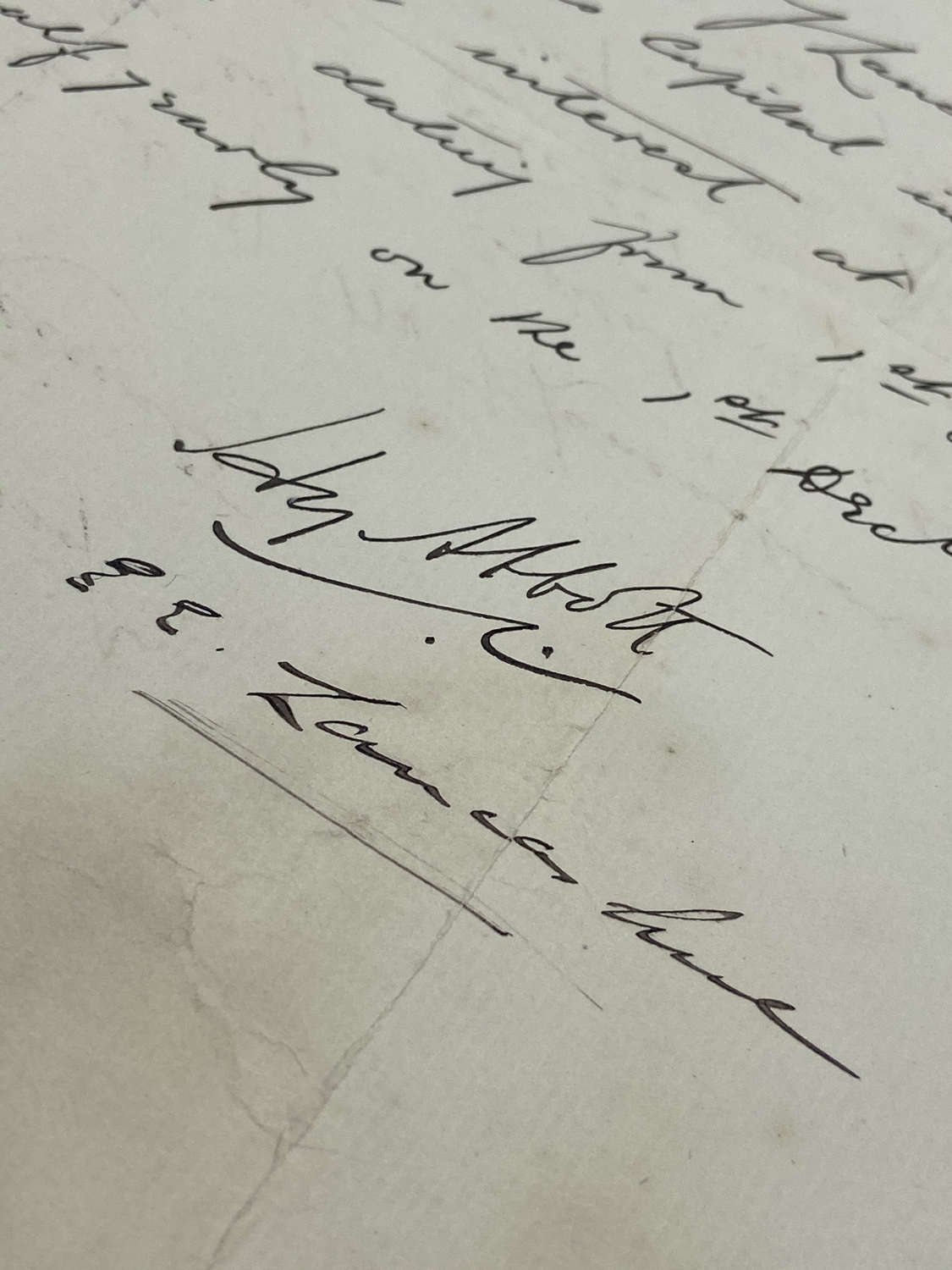

Signed by underneath:

H Abbott

E E Lancashire

One of the districts considered to have the most skilled weavers was Spitalfields in East End London, where silk-weaving had been introduced in the late 17th century by Huguenot immigrants. These skilled French weavers and local people alike who learned the trade via a lengthy apprentice period belonged to various weaver’s Guilds and created the most exclusive cloth. In particular used for every conceivable type of luxury in clothes, accessories and home furnishings. These categories included satins, velvets, brocades, watered silks, paduasoys, watered tabbies, lustrings and mantuas. Despite a multitude of ongoing disputes and restrictions as petitions, sumptuary legislations, patents, smuggling, dissatisfaction of low wages, competition from Indian calicoes etc – production prospered during most decades until the 1780s when the silk industry, like linen-weaving, ran into an even greater competition from cotton. The Spitalfields silk manufacturing is regarded to have had a downturn in the late 18th century and first made some revival around 1798.

Two further preserved trade cards are clearly linked to the silk trade. Firstly the undated mid-century rococo style (Banks, 127.3) Francis Rybot as ‘Weaver and Mercer’, which reveals details of his luxury wares – manufactured as well as sold in ‘end of Smock Alley, Spittle Fields London’. Besides a great variety of English qualities, he sold imported velvets from Holland and Genoa as well as ‘Venetian Poplins’. The second ‘Weaver and Mercer’, named William Wilson had his premises ‘at his Warehouse, Sign of the White Lion’ in the Corner of George St Minories in London (Banks, 84.106). This trade card is marked with the year 1799. The occupation ‘mercer’ indicated that he was a businessman, who sold mostly fine silks and velvets. A few other randomly preserved trade cards linked to weavers, include the weaver Isaac Bradshaw who ‘Makes Ribbons, Ferrits, &c. and sells Wholesale upon the very lowest Terms’ (Heal, 127.2). Together with a ‘Weaver and Haberdasher’ named William Poole, who in 1778 had his premises at no 53 Cheapside in London (Heal 127.18-19) and the ‘Weaver and Warehouse-man’ Joshua Warne in Newgate Street (Banks, 127.4).

To conclude with some further thoughts on the London silk weavers. Many workers lived under poor or very modest circumstances and silk qualities were often woven on commission from their own home for a master weaver. A multitude of in-depth research have been made over the last hundred years about living conditions for skilled as well as unskilled labourers of silk manufacturing in Spitalfields and other nearby areas – where poverty and wealth lived side by side. In particular by the late textile historian Natalie Rothstein during the 1950s to 1990s. Minute details are therefore known about individual master weavers, their workshops and order books, male and female silk designers, sample books, specialisation in various qualities from advanced flowered damask to plain woven silks, number of employed journeymen, female silk weavers and winders, as well as young apprentices coming and going over the years.

However, hand-written documents or prints which registered that these 18th century master weavers simultaneously acted as shop owners and manufacturers of fabric have seldom survived. The combination existed, evident via some of the illustrated and referenced trade cards, but it seems to have been quite unusual. One disadvantage for such an arrangement was the weavers’ long working hours in a specialist workshop or in their own home – assisted by apprentices, journeymen, draw boys, family members et al – which either way gave limited time to keep a time-consuming selling establishment. Especially for the hundreds of silk weavers who had their home and workplace in Spitalfields or nearby Bethnal Green, White Chapel etc – which restricted the chances for most to put their goods up for sale in such a crowded area of similarly skilled professionals. Undoubtedly, the majority of these master weavers must have had a variety of options to sell their silks. Either assisted by local silk masters or via mercers, drapers, haberdashers and wholesale warehouses in the City of London and nearby districts of the capital, or in the form of preorders from well-to-do customers in Great Britain, the British colonies or via merchants for export to other countries..

Pretty much everyone has heard of the Luddites, although many people still have a misconception about the reasons why they destroyed machinery. The weavers of Yorkshire, Nottinghamshire, Lancashire and Leicestershire smashed machine looms not because they were blindly opposed to progress, or afraid of new technology, but because the introduction of machinery was undermining the livelihoods of themselves and their communities. They viewed new technology through the eyes of artisans accustomed to a certain amount of autonomy: from being well-paid workers working mainly under their own terms, often in their own homes, they were being reduced to poverty, and clearly saw that mechanisation was transforming them into wage slaves, increasingly forced into factories. Their challenge to new technology was based on both desperation and self-interest: machine-weaving was benefitting the masters and increasing their profits, at the workers’ expense, but machines could be used to improve the lives of those who created the wealth, if their use was controlled by the workers themselves.

It’s all about who’s making the decisions, and in whose interests… A question of control, how new technological developments change our work, strengthening us or those who live off our labour; a question that remains alive and crucial today.

Less well known than the Luddites, though, another group of workers also fought the imposing of machinery and the factory system against their interests – the silk weavers of Spitalfields, in London’s East End. Four decades before the Luddite uprisings, the silkweavers’ long battle against mechanisation came to a head in violent struggles. Like the Luddites, their campaign was volatile and violent, and was viciously repressed by the authorities. But their struggles were more complex and contradictory, in that sometimes they were battling their employers and sometimes co-operating with them; to some extent they won more concessions than their northern counterparts, holding off mechanisation for a century, and maintaining some control over their wages and conditions, at least for a while.

Spitalfields is one of the oldest inhabited parts of London’s East End, and one of the earliest to be built up as the fringes of the City of London spread outward. Described as City’s “first industrial suburb”, from the Middle Ages, Spitalfields, (together with neighbouring areas Bishopsgate and Shoreditch), was well known for industry, which was able to establish here outside the overcrowded City; but also for poverty, disorder and crime. Outside the City walls, outside the jurisdiction of City authorities, the poor, criminals, and outcast and rebellious clustered here.

From medieval times the area’s major employer has been the clothing trade; but breweries have also been major employers since 17th century, and later residents formed a pool of cheap labour for the industries of the City and East End: especially in the docks, clothing, building, and furniture trades. Small workshops came to dominate employment here.

The relationship between the affluent City of London and the often poverty and misery-stricken residents over its eastern border in Spitalfields has dominated the area’s history. More than half the poor in Spitalfields worked for masters who resided in the City in 1816; today the local clothing trade depends on orders from West End fashion shops… The same old social and economic relations continue…

For similar reasons as those that led to the growth of industry and slums here, the area has always been home to large communities of migrants. Many foreigners in the middle ages could not legally live or work inside City walls (due to restrictions enforced by the authorities or the guilds), leading many to settle outside the City’s jurisdiction. Successive waves of migrants have made their homes here, and dominated the life of the area: usually, though not always, the poorest incomers, sometimes competing for the jobs of the native population, at other times deliberately hired to control wages in existing trades… Huguenot silkweavers, the Irish who were set to work undercutting them, Jewish refugees from late nineteenth-century pogroms in east Europe, and the Bengalis who have settled in the area since the 1950s…

For centuries Silk Weaving was the dominant industry in Spitalfields and neighbouring areas like Bishopsgate, Whitechapel and Bethnal Green, spreading as far as Mile End to the east, and around parts of Clerkenwell further west.

Silkweavers were incorporated as a London City Company in 1629. But many foreigners or weavers from northern England or other areas were not allowed to join the Company, and had problems working or selling their work as they weren’t members…

Silk production demanded much preparation before actual weaving began: throwing, where silk that has been reeled into skeins, is cleaned, twisted and wound onto bobbins, employed thousands in London already by the 1660s, though later throwing was dispersed to other towns.

In the early years weaving in Spitalfields was a cottage industry, with many independent workers labouring at home. This quickly developed into a situation with a smaller number of masters, who employed journeymen and a legally recognised number of apprentices to do the work. Numbers of workers, and training, in the Weavers Company were regulated by law and in the Company courts; later wages came to be a matter of dispute and the courts had to deal with this too.

Masters often sub-contracted out work to homeworkers, so that by the end of the 18th Century, many silkweavers were employed in their own homes, using patterns and silk provided by masters, and paid weekly. Later still there developed middlemen or factors, who bought woven silks at lowest prices and sold them to wholesale dealers. This led to lower wages for the weavers themselves.

A twentieth century account described the organisation of weaving in the area, based on reports from the previous century:

“The manufacturer procures his thrown ‘organzine’ and ‘tram’ either from the throwster or from the silk importers, and selects the silk necessary to execute any particular order. The weaver goes to the house or shop of his employer and receives a sufficient quantity of the material, which he takes home to his own dwelling and weaves at his own looms or sometimes at looms supplied by the manufacturer, being paid at a certain rate per ell. In a report to the Poor Law Commissioners in 1837 Dr. Kay thus describes the methods of work of a weaver and his family:-

A weaver has generally two looms, one for his wife and another for himself, and as his family increases the children are set to work at six or seven years of age to quill silk; at nine or ten years to pick silk; and at the age of twelve or thirteen (according to the size of the child) he is put to the loom to weave. A child very soon learns to weave a plain silk fabric, so as to become a proficient in that branch; a weaver has thus not unfrequently four looms on which members of his own family are employed…”

“The houses occupied by the weavers are constructed for the special convenience of their trade, having in the upper stories wide, lattice-like windows which run across almost the whole frontage of the house. These ‘lights’ are absolutely necessary in order to throw a strong light on every part of the looms, which are usually placed directly under them. Many of the roofs present a strange appearance, having ingenious bird-traps of various kinds and large birdcages, the weavers having long been famed for their skill in snaring song-birds. They used largely to supply the home market with linnets, goldfinches, chaffinches, greenfinches, and other song birds which they caught by trained ‘call-birds’ and other devices in the fields of north and east London.”

The wide high windows that shed enough light for their work can still be seen everywhere on older buildings around Spitalfields.

Although skilled, and often reasonably well-paid, the weavers could be periodically reduced to poverty; partly this was caused by depressions in cloth trade (one of the earliest recorded being that of 1620-40). “On the occurrence of a commercial crisis the loss of work occurs first among the least skilful operatives, who are discharged from work.” This, and other issues, could lead to outbreaks of rebelliousness: sometimes aimed at their bosses and betters, and sometimes at migrant workers seen as lowering wages or taking work away from ‘natives’.

For two hundred years, through the 17th and 18th centuries, the Silk Weavers of the East End conducted a long-running battle with their employers over wage levels, working conditions and increasing mechanisation in the industry. One early method of struggle was the ‘right of search’: a power won over centuries by journeymen weavers, and eventually backed by law, to search out and in some cases destroy weaving work done by ‘outsiders’, usually those working below the agreed wage rates, or by weavers who hadn’t gone through proper apprenticeships, by foreigners etc. Silkweavers used it, however, at several points from 1616 to 1675, to block the introduction of the engine loom with its multiple shuttles.

The journeymen weavers also had a history of support for radical groups, from the Leveller democrats of the English Civil War. through the 1760s populist demagogue John Wilkes, to the ‘physical force’ wing of the Chartist movement of the 1830s. This support arose partly from obvious causes – the weavers’ precarious position and sometimes uneven employment were always likely to draw a sizable number towards radical politics. But radical activists, like leveller leader John Lilburne, also camapaigned and agitated on behelf of the silkweavers, and populists like Wilkes easily tapped into their grievances… Their fierce collectivity in their own interests extended, for some, to a wider class consciousness; but also made them vulnerable to exploitation by manipulation by bosses and demagogues.

Through the later 17th to the late 18th century, the silkweavers regularly combined to fight for better conditions, often attacking masters employing machine looms, which they saw as leading to reduction of wages and dilution of their skills. At other times, the journeymen and masters united tactically to press for parliament to pass protectionist laws that kept prices for their finished goods high…

But by the 1760s tensions between masters and workers had grown to eruption point. Dissatisfaction over pay among journeymen silkweavers was increasing; and 7,072 looms were out of employment, with a slump in the trade partly caused by smuggling (carried on to a greater extent than ever). In 1762, the journeymen wrote a Book of Prices, in which they recorded the piecework rates they were prepared to work for (an increase on current rates in most cases). They had the Book printed up and delivered to the masters – who rejected it. Increasingly masters were turning to machine looms, and hiring the untrained, sometimes women and children, to operate them, in order to bypass the journeyman and traditional apprentices and their complex structure of pay and conditions.

As a result of the rejection of the Book, two thousand weavers assembled and began to break up looms and destroy materials, and went on strike. There followed a decade of struggle by weavers against their masters, with high levels of violence on both sides.

Tactics included threatening letters to employers, stonings, sabotage, riots and ‘skimmingtons’ (mocking community humiliation of weavers working below agreed wage levels: offenders were mounted on an ass backwards & driven through the streets, to the accompaniment of ‘rough music’ played on pots and pans). The battle escalated to open warfare, involving the army, secret subversive groups of weavers, (known as ‘cutters’ for their tactic of slashing silk on offending masters’ looms), and ended in murder and execution. Some of these tactics had long roots in local history and tradition – others could have been imported with irish migrants from the Whiteboy movement in Ireland.

In 1763 thousands of weavers took part in wage riots & machine smashings, armed with cutlasses and disguised, destroying looms: “in riotous manner [they] broke open the house of one of their masters, destroyed his looms, and cut a great quantity of silk to pieces, after which they placed his effigy in a cart, with a halter about his neck, an executioner on one side, and a coffin on the other; and after drawing it through the streets they hanged it on a gibbet, then burnt it to ashes and afterwards dispersed.” [From the “Gentleman’s Magazine”, November 1763]

The military occupied parts of Spitalfields in response.

Riots and demonstrations continued in 1764-5… As a result of these riots, an Act was passed in 1765 declaring it to be felony and punishable with death to break into any house or shop with intent maliciously to damage or destroy any silk goods in the process of manufacture: this was to be used with devastating effect four years later.

In 1767 wage disputes broke out again: masters who had reduced piece rates had silk cut from their looms. At a hearing in the Weavers Court, in November that year, a case was heard, in which a number of journeymen demanded the 1762 prices from their Book be agreed. The Court agreed that some masters had caused trouble by reducing wages and ruled that they should abide by the Book. However this had little effect, and trouble carried on sporadically.

Trouble was also breaking out between groups of workers: single loom weavers and engine looms weavers were now at loggerheads. On 30 November 1767, “a body of weavers, armed with rusty swords, pistols and other offensive weapons, assembled at a house on Saffron-hill, with an intent to destroy the work of an eminent weaver without much mischief. Some of them were apprehended, and being examined before the justices at Hicks-hall, it appeared that two classes of weavers were mutually combined to distress each other, namely the engine weavers and the narrow weavers. The men who were taken up were engine weavers, and they urged… that they only assembled in order to protect themselves from a party of the others who were expected to rise. As they had done no mischief, they were dismissed with a severe reprimand…”

The events of 1762-7 were, however, merely a curtain raiser, for the cataclysmic struggles of 1768-69. The ‘Cutters’ Riots’ saw a prolonged struggle, with bitter violence, rioting, intimidation of workers and threatening letters to employers, and hundreds of raids on factories and small workshops. Strikers in other trades joined in the mayhem: 1768. Crowds of weavers also forcibly set their own prices in the food markets, in defiance of high prices. It would end in shootouts in a pub, and executions.

In the Summer of 1769, some of the masters attempted to force a cut in rates of pay. In response, some journeymen banded together to organise resistance, forming secret clubs, including one allegedly called the Bold Defiance, (or Conquering and Bold Defiance, or the Defiance Sloop). This group met at the Dolphin Tavern in Cock Lane, (modern Boundary Street, in Bethnal Green). The Bold Defiance started raising a fighting fund, as part of which they attempted to levy a tax on anyone who owned or worked a loom. Their methods of fund-raising bordered, shall we say, on extortion, expressed in the delivery to silk weaving masters of Captain Swing-style notes: “Mr Hill, you are desired to send the full donation of all your looms to the Dolphin in Cock Lane. This from the conquering and bold Defiance to be levied four shillings per loom.”

One major silk boss threatened by the cutters was Lewis Chauvet, whose factory stood in Crispin Street, Spitalfields. A leading manufacturer of silk handkerchiefs, who had already been involved in bitter battles against striking weavers in Dublin, Chauvet banned his workers from joining the weavers’ clubs or paying any levies, and organised a private guard on his looms. As a result, the cutters gathered in large numbers and tried to force Chauvet’s workers to pay up. Fights broke out and many people on both sides were badly hurt. Then, on the night of Thursday 17th August, the cutters assembled in gangs and went to the homes of Chauvet’s workers, cutting the silk out of more than fifty looms. Four nights later, on Monday 21st, they gathered in even greater numbers and cut the silk out of more than a hundred looms. Throughout the night the streets of Spitalfields resounded to the noise of pistols being fired in the air.

Chauvet’s response to this episode was to advertise a reward of £500 for information leading to the arrest of those responsible. But for several weeks the people of Spitalfields remained silent, either for fear of the cutters, or because they did not wish to give evidence that might send a man to the gallows.

But on the 26th September, a minor master weaver, Thomas Poor, and his wife Mary, swore in front of a magistrate that their seven looms had been slashed by a group of cutters led by John Doyle and John Valline. However, before giving evidence they had inquire with Chauvet about receiving the reward – and Doyle had already been arrested, so they may have been prompted to name them… Certainly Doyle and Valline later protested their innocence.

On 30 September 1769, after a tip off from a master weaver who had had the squeeze put on him, magistrates, Bow St Runners and troops raided the Bold Defiance’ HQ at the Dolphin Tavern, finding the cutters assembled in an upstairs room, armed, and “receiving the contributions of terrified manufacturers.” A firefight started between the weavers and the soldiers and runners, which left two weavers (including a bystander) and a soldier dead; but the cutters escaped through the windows and over rooves. Four weavers who were drinking in the pub downstairs, and one found in bed upstairs were arrested, and held for a few weeks; though no-one was brought to court over the deaths.

But Valline and Doyle were convicted of the attack on the Poor’s looms and sentenced to death under the 1765 Act, despite very dubious identification evidence. They were hanged on the 6th December 1769, at corner of Bethnal Green Road and Cambridge Heath Road opposite the Salmon and Ball pub. Though Tyburn was the usual place of execution, the major silk manufacturers pressured the authorities to have them ‘scragged’ locally, to put the fear of god on the rebellious weavers. An organised attempt to free them was planned, and the men building the gallows were attacked with stones:

“There was an inconceivable number of people assembled, and many bricks, tiles, stones &c thrown while the gallows was fixing, and a great apprehension of a general tumult, notwithstanding the persuasion and endeavours of several gentlemen to appease the same. The unhappy sufferers were therefore obliged to be turned off before the usual time allowed on such occasions, which was about 11 o’clock; when, after hanging about fifty minutes they were cut down and delivered to their friends.”

Doyle and Valline were offed, proclaiming themselves not guilty of the silk cutting. After their execution the crowd tore down the gallows, rebuilt them in front of Chauvet’s factory/house here in Crispin Street, and 5,000 people gathered to smash the windows and burn his furniture.

Two weeks later on December 20th, more cutters were executed: William Eastman, William Horsford (or Horsfield) and John Carmichael. Horsfield had also been implicated by the Poors; Daniel Clarke, another silk pattern drawer and small employer, was paid by Chauvet to give evidence against Eastman, who he claimed had cut silk on Clarke’s looms. Clarke had previously tried to undercut agreed wage rates, and had it seems testified before against insurgent weavers, in his native Dublin. Clarke had originally told friends that he couldn’t identify the men who’d cut his silk, but after contact with Chauvet miraculously his memory changed. It’s possible Eastman was a cutters’ leader Chauvet wanted out of the way; Clarke also named one Philip Gosset, locally suggested to be the chairman of one of the cutters’ committees (Gosset, however, was never caught). Contradictory evidence, protests, a weavers’ march on Parliament to ask for pardon, all fell on deaf ears: the authorities were determined to make examples of the accused. This time, though, afraid of the local reaction after the riots that followed the deaths of Doyle and Valline, they were executed at Tyburn.

Although the repression quietened things down for a year or so, these hangings still had a twist to come. On 16th April 1771, the informer, Daniel Clarke was spotted walking through Spitalfields streets, and chased by a crowd of mainly women and boys, including the widow of William Horsford. He was finally caught, and dunked in the Hare Street Pond, a flooded gravel pit in Bethnal Green; the crowd stoned and abused him, and after they let him out of the pond he collapsed and died.

In Spitalfields this was widely seen as community justice – but the official ‘justices’ had to squash another open challenge to law and order. Two more weavers, Henry Stroud – William Eastman’s brother in law – and Robert Campbell were hanged on July 8th for Clarke’s ‘murder’; once again, local punishment was deemed necessary to overawe the uppity weavers, and they were stretched in Hare Street. Horsford’s widow, Anstis, was also charged with murder, but wasn’t executed (possibly she was acquitted, I’ve had trouble following the case reports!). Witnesses had to be bribed to testify, and were attacked; Justice Wilmot, who arrested the two men, only just escaped the justice of an angry crowd, and a hundred soldiers had to be posted to ensure the hanging took place.

Although prices were fixed between masters and workers, nothing obliged the masters to keep to them. In 1773, further discontent broke out. Handbills circulated, addressed to weavers, coalheavers, porters and carmen (cartdrivers), to ‘Rise’ and petition the king. Silkweavers met at Moorfields on April 26th, incited by another handbill that read “Suffer yourselves no longer to be persecuted by a set of miscreants, whose way to Riches and power lays through your Families and by every attempt to starve and Enslave you…” Magistrates however met with them, and persuaded them to disperse, promising them a lasting deal.

This materialised in the form of the Spitalfields Acts. The first Act, in 1773, laid down that wages for journeymen weavers were to be set, and maintained, at a reasonable level by the local Magistrates, (in Middlesex) or the Lord Mayor or Aldermen (in the City). Employers who broke the agreed rate would be fined £50; journeymen who demanded more would also be punished, and silk weavers were prohibited from having more than two apprentices at one time. The Acts were renewed for 50 years, and ensured that some weavers, at least, had some security if income and protection for unscrupulous employers… The Acts’ abolition in the 1820s was a cause celebre for the laissez-faire capitalists of the days – and helped to drive silkweavers into catastrophic poverty and decimate the trade locally.

This letter belongs in a museum! Very little of these are left in the hands of private collectors, all are in special collections and history museums.